DR.

J'S ILLUSTRATED LECTURES

The

Illustrated Mythic Hero

Illustrated Greek Theater

Illustrated Greek Drama

Illustrated Parthenon Marbles

Illustrated Road to the Recovery of

Ancient Buildings

Illustrated Greek History MENU

Bronze Age

Archaic Age

Persian Wars

Classical Age

|

|

| Dr. J's

Illustrated Persian Wars |

| The Classical Age begins with the

monumental Greek victory over the Persians in what have become known to us as the Persian

Wars. Pericles makes reference to these wars when he boasts about the previous generation

of Athenians' success in "stemming the tide of foreign aggression." The Persian

Wars were really a series of Persian versus Greek battles, in which Greek citizens from

many city-states fought against the barbarian (as they saw it) invaders. The Persian Wars

are said to have been provoked by the gradual rejection of Persian authority by the Greek

colonies along the Ionian coast (across the Aegean Sea from Athens, on the shore of the

continent of Asia) from 499-494 BC. Living in the shadow of the Persian Empire, and

tired of paying tribute, some of the colonies (founded during the Archaic period during

the Age of Expansion/Colonization) tried flexing their muscles and were immediately and

utterly trounced by the much more formidable Persians. Once the Persians invaded

Eretria,

one of the big naysayers, and enslaved her population, Athens (Persia's next target) knew

that trouble was coming down the pike and prepared as best she could... |

The

Battle Of Marathon (490 BC) |

Herodotus assures us that the Greek victory

that stunned both sides was the result of a shrewd battleplan: the great Athenian general

Miltiades chose not to deploy his troops in the traditional way, with the bulk of his men

in the middle of a phalanx of soldiers. Instead, he thinned out the ranks in the center,

giving the Persians a false sense of imminent victory. After the Persians easily broke

through the ranks, they were swarmed by Greek soldiers attacking from the flanks

(Athenians from one side and Plataeans from the other). Herodotus also tells us that for

the first time Athenian slaves were freed so that they could fight for the Athenian cause.

After the battle, the Athenians built this treasury (photo upper left) at Delphi to hold

all their votive offerings to the oracle. Herodotus assures us that the Greek victory

that stunned both sides was the result of a shrewd battleplan: the great Athenian general

Miltiades chose not to deploy his troops in the traditional way, with the bulk of his men

in the middle of a phalanx of soldiers. Instead, he thinned out the ranks in the center,

giving the Persians a false sense of imminent victory. After the Persians easily broke

through the ranks, they were swarmed by Greek soldiers attacking from the flanks

(Athenians from one side and Plataeans from the other). Herodotus also tells us that for

the first time Athenian slaves were freed so that they could fight for the Athenian cause.

After the battle, the Athenians built this treasury (photo upper left) at Delphi to hold

all their votive offerings to the oracle.The Battle of Marathon spawned legends immediately: witnesses

swore that the ghost of Theseus (mythical king of Athens) loomed over the field, giving

confidence to his countrymen; the messenger Phidippides is said to have run into the god

Pan on his way to ask for help from the Spartans and received the god's help instead (and

too, the old story about how he died after running the equivalent of 26 miles to deliver

news of the victory at Marathon is not supported by any ancient source...); and some say

that the clash of arms can still be heard today on the Plain of Marathon at night.

The story of a victory run from Marathon to Athens first appears in

Plutarch's Moralia (347C) over half a millennium later than the Persian Wars;

he gives credit to either Thersippus or Eukles. Lucian, in the second

century AD, says that a PhiLippides ran from Marathon.

The story is probably a confused version of the even more astounding run

that Herodotus tells us PhiDippides completed from Athens to Sparta just

BEFORE the battle. He went to seek Spartan aid and took 2 days to run the

145 miles between the two cities -- an impressive, but not unbelievable feat

(Hdt. 6.105-6) |

| Pausanias (1.33.2) tells us that

the Persians were so sure of victory that they had brought with them a block of marble to

be carved into a victory monument. Instead, the great Athenian sculptor Pheidias carved it

into a statue of the god Nemesis, avenger of wicked actions, plainly indicating that the

Persians got exactly what they deserved. See Book 6 of Herodotus' History

for a full report on the 490 BC Battle of Marathon. |

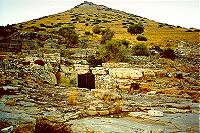

On the left is

the soros on site at Marathon, the burial place for the 192

Athenian soldiers who died fighting the Persians in the battle. Schliemann originally

incorrectly dated this site to the Bronze Age (an actual Bronze Age

tholos does lie very close by). But later Greek archaeological excavations confirmed

this to be the grave mound known from classical tradition. They determined that an

artificial floor 85 feet long was constructed for the purpose of a mass cremation,

followed by animal sacrifices and a funeral banquet, remains of which have also been

found. The mound (eroded from its original 14 meters to its present height of only 9 On the left is

the soros on site at Marathon, the burial place for the 192

Athenian soldiers who died fighting the Persians in the battle. Schliemann originally

incorrectly dated this site to the Bronze Age (an actual Bronze Age

tholos does lie very close by). But later Greek archaeological excavations confirmed

this to be the grave mound known from classical tradition. They determined that an

artificial floor 85 feet long was constructed for the purpose of a mass cremation,

followed by animal sacrifices and a funeral banquet, remains of which have also been

found. The mound (eroded from its original 14 meters to its present height of only 9 meters) was then heaped on top. Pausanias comments that even in his day

(2nd century AD) the men who died at Marathon were worshipped as heroes. A modern

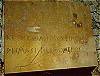

reconstruction of the ancient memorial listing the names of the dead by tribe is on

display as well (right). meters) was then heaped on top. Pausanias comments that even in his day

(2nd century AD) the men who died at Marathon were worshipped as heroes. A modern

reconstruction of the ancient memorial listing the names of the dead by tribe is on

display as well (right). Because

the small city of Plataea had sent their entire fighting force (1000 men) to help Athens

in their stand-off against the Persians at Marathon, their dead, too, were honored with a

tomb on site. Near the soros, another tumulus stands 4 meters

tall and spans 30 meters in diameter: the Tomb of the Plataeans. Marinatos' 1970

excavations uncovered 11 burials: 8 inhumations (skeleton burials, 2 of which are pictured

below), 2 cremations and 1 pithos-burial (a child, probably a later addition).

|

An

Interlude:

Athenian Silver Strike at Laurion (483 BC) |

Nobody was

surprised that the Greeks won the Battle of Marathon more than the Greeks. They reveled in

their victory - especially the Athenians, who almost single-handedly had achieved the

victory (since the Spartans arrived too late to help and the Plataeans only helped bolster

the Greek line). And when everything was going along so well, things got even better - in

483 BC, the Athenians struck a rich vein of silver in one of their mines in Laurion (near

Sounion). The photo on the left shows one of Pericles' silver mines, in use since Mycenean

times. Nobody was

surprised that the Greeks won the Battle of Marathon more than the Greeks. They reveled in

their victory - especially the Athenians, who almost single-handedly had achieved the

victory (since the Spartans arrived too late to help and the Plataeans only helped bolster

the Greek line). And when everything was going along so well, things got even better - in

483 BC, the Athenians struck a rich vein of silver in one of their mines in Laurion (near

Sounion). The photo on the left shows one of Pericles' silver mines, in use since Mycenean

times. Once mined, the silver ore was placed in

a vat and washed: it is easy to screen the silver out this way, since dirt is lighter than

silver, and silver lighter than lead. The photo on the right shows a reconstructed ore

washer. Go here for

a more detailed explanation of Athenian silver mining by Andrew Wilson. Once mined, the silver ore was placed in

a vat and washed: it is easy to screen the silver out this way, since dirt is lighter than

silver, and silver lighter than lead. The photo on the right shows a reconstructed ore

washer. Go here for

a more detailed explanation of Athenian silver mining by Andrew Wilson. |

| After lengthy arguments, the Athenians

decided to invest their new-found fortune in a fleet of 200 ships, for the purpose of

commerce and protection. It was this silver strike that enabled the Athenians to be the

first Greek city-state to mint its own silver coins, too. This new-found wealth and the

use to which it is put is what allows Athens to become the superior power among all Greek

city-states in the fifth century. |

While the penteconter

was the

old-style ship from previous eras, the new fleet which Athens would turn against the

Persians at Salamis was primarily composed of triremes. Learn more about triremes.

To the left is the obverse of the modern Greek 50 drachma coin,

an homage to Greek ships of the past. While the penteconter

was the

old-style ship from previous eras, the new fleet which Athens would turn against the

Persians at Salamis was primarily composed of triremes. Learn more about triremes.

To the left is the obverse of the modern Greek 50 drachma coin,

an homage to Greek ships of the past. |

The

Battle of Thermopylae (480 BC) |

| Much like in antiquity,

Thermopylae (called "Hot Gates" because it marks a narrow passage beyond which

lie hot springs) is situated along the road from northern to central/southern Greece. In

fact, even though the topography has changed since antiquity (the sea used to be closer),

the National Road pretty much follows the same route Xerxes' Persians forces did. All

agree that the forces were not equally matched, although Herodotus' numbers cannot

be right: he would have us believe that several thousand Greeks stood against over 5

million Persians. It is more likely that the Persian forces numbered about 300,000 against

the Greek's 7-8000. |

| The

Persians were so disheartened after the first day of fighting that they had to be whipped

into action (literally) the next day. With the help of a Greek turncoat, the Persians were

able to side-step Greek (Phocian) precautionary measures and approach the actual pass in

force. The Spartan commander Leonides dismissed all allies present (from nearly every

Peloponnesian city) except the Thebans and his own band of 300 crack fighting men. The

hand-to-hand combat grew so bloody that it is said that Xerxes rose three times from his

throne in horror at the losses. Leonides and his band fought to the last man, the

surviving Thebans were captured, and the Persians resumed their advance on Athens. |

This

modern memorial to the men who died defending the pass at Thermopylae was erected in 1955

(and was funded by America!); the bronze statue of Leonides was modeled after a fifth

century marble statue presently housed This

modern memorial to the men who died defending the pass at Thermopylae was erected in 1955

(and was funded by America!); the bronze statue of Leonides was modeled after a fifth

century marble statue presently housed in the Sparta museum. The

marble base of the memorial is composed of reliefs showing scenes from the battle and

bronze plaques bearing famous epigrams inspired by this conflict (photo on right). in the Sparta museum. The

marble base of the memorial is composed of reliefs showing scenes from the battle and

bronze plaques bearing famous epigrams inspired by this conflict (photo on right). |

|

The

Battle of Salamis (480 BC) |

It is due to

Themistokles' powers of persuasion that the Athenians suffered

no loss of life when the Persians marched into Athens and burned it to the ground. The

Oracle of Delphi had warned that everything Athenian would be burned to the ground except

for what lay behind a wooden wall: some thought that meant that the populace should huddle

within the walls of the Acropolis and try to outlast a Persian siege. But Themistokles

rightly concluded that the "wooden wall" referred to the battleline of the great

Athenian warships. So when the Persians did march into Athens and burn down the city, the

women and children had already been transported safely to the nearby city of Troezen

(birthplace of Theseus), the old men were taken to the nearby island of Salamis, and only

those few who remained behind the walls lost their lives. It is due to

Themistokles' powers of persuasion that the Athenians suffered

no loss of life when the Persians marched into Athens and burned it to the ground. The

Oracle of Delphi had warned that everything Athenian would be burned to the ground except

for what lay behind a wooden wall: some thought that meant that the populace should huddle

within the walls of the Acropolis and try to outlast a Persian siege. But Themistokles

rightly concluded that the "wooden wall" referred to the battleline of the great

Athenian warships. So when the Persians did march into Athens and burn down the city, the

women and children had already been transported safely to the nearby city of Troezen

(birthplace of Theseus), the old men were taken to the nearby island of Salamis, and only

those few who remained behind the walls lost their lives. |

| See Herodotus (8:70-94) and

Aeschylus' play The Persians for ancient accounts of this battle. Scholars still

argue over the details, which can be pretty overwhelming, but the basic facts are these:

acting on false intelligence information planted by the Greeks, the Persians positioned

their fleet at the mouth of the Bay of Salamis, thinking to catch the Greek sailors before

they could man their ships in the morning. But dawn caught them walking right into a Greek

trap - as the Persian ships poured into the bay, the Greek ships, hiding in the channel

beyond the bay, rammed them broadside. The large number of Persian ships and the small

diameter of the bay made it difficult for the Persians to maneuver (one story in

particular tells of one Persian ship sinking another). The Greek victory at the Battle of

Salamis forced Xerxes to hightail it home, but the Persian threat wasn't over by a long

shot. |

|

The

Battle of Plataea (479 BC) |

| In the Battle of Plataea

(north of Athens, on the border between Attica and Boeotia), a combined Greek force (from

31 different city-states!) helped ward off the enemy Persians and their Greek allies the

Thebans, who had "medised" or "gone Persian" during these wars against

her own Greek brethren (it is probable that even Thebes' participation in the Battle of

Thermopylae was under duress - i.e., Leonides forced them to stay and defend the pass). In

this final battle of the Persian Wars, the Spartans killed the Persian general Mardonius

(whose sword is thereafter displayed in the Erechtheum on the Athenian

Acropolis as a spoil of war) and the Athenians decimated the Theban Sacred Band. |

| Fifty years later, though, Thebes will

exact retribution from the Athenian-allied Plataeans: theirs is one of the first cities

ravaged by Thebes in the 431 BC campaigns of the Peloponnesian War, the year of war

commemorated by Pericles in his famous Funeral Oration. And, of course, soon Athens and

Sparta will no longer be "Hellenic" allies fighting against a "foreign

aggressor," but enemies in their own right (as alluded to by Pericles in that same

speech). See Herodotus 9.19 for a full report on the 479 BC Battle of

Plataea.

|

|

The frieze of the

Temple of Athena Nike on the Acropolis (built during the Peloponnesian War) trumpets the

Athenian victory at that very Battle of Plataea - it is most remarkable for the frieze of

a Temple (especially one dedicated to Athena!) to relate an historical - not mythological -

battle. We are reminded that "Nike" means "Victory." |

In Delphi we can

still today see the base of the Tripod of the Plataeans, erected to commemorate the

victory of the Greek city-states over the Persian army at Plataea in 479 BC

(Pausanias

X.13.9). The monument commands an important space, as it sits directly across the Sacred

Way from the Altar of the Temple of Apollo yet is not blocked by it. Originally a golden

victory tripod stood atop three twisted snake columns upon which were inscribed the names

of the 31 city-states who contributed to the victory. The Emperor Constantine the Great

(early 4th century AD) removed the columns to Constantinople, where half of it remains

today on display in the Hippodrome. In Delphi we can

still today see the base of the Tripod of the Plataeans, erected to commemorate the

victory of the Greek city-states over the Persian army at Plataea in 479 BC

(Pausanias

X.13.9). The monument commands an important space, as it sits directly across the Sacred

Way from the Altar of the Temple of Apollo yet is not blocked by it. Originally a golden

victory tripod stood atop three twisted snake columns upon which were inscribed the names

of the 31 city-states who contributed to the victory. The Emperor Constantine the Great

(early 4th century AD) removed the columns to Constantinople, where half of it remains

today on display in the Hippodrome.

copyright

2001 Janice

Siegel,

All Rights Reserved

send comments to: Janice Siegel (jfsiege@ilstu.edu)

date this page was edited last:

08/02/2005

the URL

of this page:

|

|