DR.

J'S ILLUSTRATED LECTURES

The

Illustrated Mythic Hero

Illustrated Greek Theater

Illustrated Greek Drama

Illustrated Parthenon Marbles

Illustrated Road to the Recovery of

Ancient Buildings

Illustrated Greek History MENU

Bronze Age

Archaic Age

Persian Wars

Classical Age

|

|

Dr.

J's Illustrated Archaic Age

color-coded

Timeline/Lecture

war

literature/theater

politics

science/philosophy

Panhellenic

Festivals

It

turned out to be more difficult than I thought to assign colors to

various aspects of Greek history. And this speaks to the very nature of

ancient Greek culture: spheres of influence were not so easily divisible

in ancient Greece as they are for us. The Greeks had an uncanny facility

to move easily from the sacred sphere to the political to the

domestic... it makes me mourn the loss of that totality of experience in

our own culture. Back then, kings consulted religious Oracles on matters

of State, athletes at Panhellenic Games sought glory for their home

cities from the particular Olympic god to whom the games were dedicated,

and the God Dionysus himself - in the figure of his cult statue -

presided over theatrical competitions in fifth century Athens. Is Attic

theater an artistic invention? A political tool? A religious event? All

of the above. How can we define "philosopher"? The cosmologist

Pythagoras attracts a religious following; Socrates becomes a political

subversive; Aristotle invents literary theory. What an amazing time, and

what amazing people.

The

Archaic Age is characterized by a Greek spirit of unity not quite strong

enough to unite the cities politically, but definitely strong enough to

remind them of their common bond. This busy time has been described as

The Age of Aristocracies, The Age of Expansion, The Beginning of the

Western Literary Tradition, and the Age of Law-Givers. The first thing

we notice is that there are no really big wars in this age, and people

are busy developing culture: Panhellenic

Festivals, theater,

law codes, literature,

democracy,

and early

Greek science and philosophy

all hark back to the Archaic Age.

|

Age

of Aristocracies

|

The

Archaic Age is best known as the Age of Aristocracies, because

its developing poleis (city-states) are

characterized by a rejection of the old-style monarchies of

the Mycenean Age (as

dramatized in later plays you may have read such as Aeschylus'

Agamemnon and Sophocles' Oedipus).

The

Archaic Age is also characterized by the development of

Panhellenic Centers, one of the first signs that Greece is

coming out of the previous period, known as the Dark Age. The

destruction of Mycenean civilization caused a fearful time in

which the Greeks of each area kept to themselves (which is

very easy to do in Greece since the mountainous topography

naturally isolates each habitable area from the next). The

establishment of the Panhellenic ("All-Greece")

Festival at Olympia (in honor Zeus) is the first sign that

Greeks are beginning to communicate and interact with each

other again. They came from all over to compete for the honor

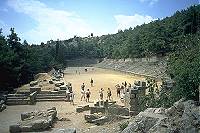

of their home city-state. OLYMPIA

is a city in the Peloponnesus (southern part of Greece), named

in honor of Zeus, King of the Olympian gods; don't confuse it

with MT.

OLYMPOS, the mountain home to the OLYMPIAN gods. On the

left is a photo of the Palaestra at Olympia, where the

athletes practiced, although the ancient

competitions were not restricted to athletic events, as

they are today.

The

Archaic Age is best known as the Age of Aristocracies, because

its developing poleis (city-states) are

characterized by a rejection of the old-style monarchies of

the Mycenean Age (as

dramatized in later plays you may have read such as Aeschylus'

Agamemnon and Sophocles' Oedipus).

The

Archaic Age is also characterized by the development of

Panhellenic Centers, one of the first signs that Greece is

coming out of the previous period, known as the Dark Age. The

destruction of Mycenean civilization caused a fearful time in

which the Greeks of each area kept to themselves (which is

very easy to do in Greece since the mountainous topography

naturally isolates each habitable area from the next). The

establishment of the Panhellenic ("All-Greece")

Festival at Olympia (in honor Zeus) is the first sign that

Greeks are beginning to communicate and interact with each

other again. They came from all over to compete for the honor

of their home city-state. OLYMPIA

is a city in the Peloponnesus (southern part of Greece), named

in honor of Zeus, King of the Olympian gods; don't confuse it

with MT.

OLYMPOS, the mountain home to the OLYMPIAN gods. On the

left is a photo of the Palaestra at Olympia, where the

athletes practiced, although the ancient

competitions were not restricted to athletic events, as

they are today.

|

|

Age

of Expansion: 750-550 B.C.

|

| From

750-550 B.C., Greek civilization revitalized. In response to

rapid population growth and a lack of arable land (grapes and

olives are about the only crops that thrive), a new

breed of Greeks sets out to discover or forge a new world.

Colonists ranged far and wide, east to the Ionian Coast of

Asia Minor, South to the northern shores of Africa, and west

to Europe: Marseilles was originally a Greek colony, and

Sicily and southern Italy has so many settlements on it it was

known as Magna Graecia, or "Big Greece." Many

of these settlements opened trade routes for Greece that

helped them become a world player in the centuries to come.

(Temple students, see your map on page 12 of your IH Source

Book - all the shaded areas are colonies dating to this

period.)

The

photos above (well, they will be soon!) are of Paestum

(originally called Poseidonia) in Italy, a Greek colony

founded by Greeks from Achaea (mid-Peloponessus) in honor of

the god of the sea, Poseidon. These are some of the most

breathtaking archaic temples that exist today. On the left, a

temple to Hera, on the right, one to Demeter, and the temple

in the middle - under the tent - is dedicated to Poseidon.

|

|

The

Western Literary Tradition begins with poetry

|

| The

Western literary tradition begins with the works of Homer and

Hesiod, dating to the mid 8th century B.C. The epic poet Homer

codified and wrote down the stories of the Trojan War (in his

Iliad and Odyssey) told orally for hundreds of years since the

actual war was fought (ca. 1250 B.C.). The didactic poetry of

Hesiod (author of Theogony and Works and Days) links everyday

life (especially for farmers) with the world of the

gods. Both authors are throwbacks to an earlier time, the

long-lost Mycenean Age (Bronze Age) when gods and man walked

the earth together (thank you, Xena...) and all Greeks were a

unified force and a more homogenous culture (i.e., it was all

Greeks against a common outside enemy, the Trojans, back then,

not one Greek against Greek another).

But

the Archaic Age, on the other hand, is witness to the

development of individually distinguishable city-states. And

it is this strain of individuality and self-expression that

paves the way for the next literary development, the lyric

poem. The lyric poets flourished in the newly colonized Asia

Minor shoreline and islands in the late 7th century B.C. (the

lower 600's B.C.). Sappho's birthdate, for example, is

estimated at ca. 610 B.C. Greek lyric poetry offers an

alternative to Homer's epic or Hesiod's didactic poetry. While

epic poetry reflects the totality of a culture, lyric poetry

is more concerned with communicating personal sentiment -

feelings of love, grief, friendship, etc. The lyric poetry of

Sappho and the other famed eight lyric poets of her age

provides a personal voice new to Greek literature and imitated

by generations of poets thereafter.

|

|

Age

of Law-Givers 621 - 594 B.C.

|

| The

last half of the 7th century B.C. is known as the Age of

Law-Givers in Greece. Draco's Law Code in Athens in 621 B.C.

caused tradition and custom to become written law for the

first time. This is a photo of the Law Code of Gortyn (SOON!),

in Crete, but Draco's Law also would have been similarly

carved into stone and publicly displayed. Draco's Code was

considered harsh, but his goal was to lessen the discrepancy

between the haves and the have-nots, economically speaking.

But despite Draco's attempts, poor people still suffered at

the hands of unscrupulous land-owners and people had gripes.

Often there were spontaneous revolts by the underprivileged

classes who could no longer bear the burden of their place in

society. The stage was set for some serious reform.

Enter

Solon the Law-Giver in 594 B.C. Solon, one of the proverbial

Seven Ancient Sages, did not hail from Athens, or even from

mainland Greece. He was one of the traveling wise men who

learned lessons from the way varied cultures handled their

challenges. Solon was given the power to re-distribute the

wealth across the board, providing welcome opportunities for

society's have-nots. Many farmers did not own the land they

worked in the first place, or they accrued debts they couldn't

pay and became sharecroppers as a result. Solon cancelled or

reduced debts and redistributed the land, restoring property

to many. Solon encouraged the production and export of olive

oil, lured foreign craftsmen with the promise of citizenship,

and made it a law that all fathers should teach their son a

trade. The Athenian pottery business grew from this edict, and

it explains why Athenian pots are found all over the

Mediterranean and beyond. Solon single-handedly created a

merchant class. He also created the first citizen-manned

courts, giving the people valuable experience in

self-government.

|

|

Age

of Tyrants in Athens: 561 - 510 B.C.

|

Pesistratus

becomes Tyrant of Athens. Back then, "tyrant" just

meant something like "the buck starts and stops

here" - he was the sole ruling body in the land, an

aristocrat's aristocrat - not necessarily a cruel and

megalomaniac ruler. Although totalitarian about making laws,

Pesistratus did have Athens' interest at heart. Under his

rule, the city prospered: he built an aqueduct, redistributed

confiscated land, helped poor farmers. Characteristic of

tyrannical rule is the desire to build monumental edifices,

proofs of the tyrant's power. The Temple

of Olympian Zeus, right, was designed to be the largest

temple in Greece (remember - the Parthenon

won't be built until 447, over 100 years later). But

Pesistratus didn't finish it; the Roman Emperor Hadrian did

- 700 years later! Pesistratus rules until 528 B.C., when his

sons Hippias and Hipparchus take over. Pesistratus

becomes Tyrant of Athens. Back then, "tyrant" just

meant something like "the buck starts and stops

here" - he was the sole ruling body in the land, an

aristocrat's aristocrat - not necessarily a cruel and

megalomaniac ruler. Although totalitarian about making laws,

Pesistratus did have Athens' interest at heart. Under his

rule, the city prospered: he built an aqueduct, redistributed

confiscated land, helped poor farmers. Characteristic of

tyrannical rule is the desire to build monumental edifices,

proofs of the tyrant's power. The Temple

of Olympian Zeus, right, was designed to be the largest

temple in Greece (remember - the Parthenon

won't be built until 447, over 100 years later). But

Pesistratus didn't finish it; the Roman Emperor Hadrian did

- 700 years later! Pesistratus rules until 528 B.C., when his

sons Hippias and Hipparchus take over. |

|

The

Institution of the Theater 534 B.C.

|

One

of Pesistratus' accomplishments was to found the institution

of the theater in Athens. Thespis wins the the 1st competition

of the new Great Dionysia Festival at Athens, featuring public

productions of tragic drama in honor of the god Dionysus, in

an early version of this theater (right) on the south slope of

the Acropolis. Around this time the tradition of publicly

reciting Homer at the Panathenaic Festival began, too. This

was the beginning of democratic idealism: making culture

available to everyone, instead of just a few. The Pesistratid

tyranny will last only another 25 years or so, and then

democracy will take hold in Athens. But the cultural

institutions he founded lived on. One

of Pesistratus' accomplishments was to found the institution

of the theater in Athens. Thespis wins the the 1st competition

of the new Great Dionysia Festival at Athens, featuring public

productions of tragic drama in honor of the god Dionysus, in

an early version of this theater (right) on the south slope of

the Acropolis. Around this time the tradition of publicly

reciting Homer at the Panathenaic Festival began, too. This

was the beginning of democratic idealism: making culture

available to everyone, instead of just a few. The Pesistratid

tyranny will last only another 25 years or so, and then

democracy will take hold in Athens. But the cultural

institutions he founded lived on. |

|

The

Beginnings of Democracy 510 B.C.

|

In

510, Cleisthenes takes power - after the assassinations of

Hippias and Hipparchus - and completely reforms the Athenian

constitution, diluting the power of the aristocracy. His

reforms establish the Council of the 500, the Board of

Strategoi (Ten Generals), and a popular court system replaces

the aristocratically-run Council of the Areopagus,

which continues to preside only over murder cases. Cleisthenes

accomplishes all of this by drawing on both the Greek love of

competition (as seen in the Olympics and in the theater

contests), and on their equally strong love of individuality.

He artificially creates new tribes (replacing the old

aristocratic tribal loyalties) which are composed of

inhabitants of various demes (territorial divisions). Each

tribe has members drawn from demes from three different

regions - inland, coast and city. So these new

"teams" (think "color-war") are all equal

in their diversity, since each one has constituents from all

over - no one slice of society (city merchants, sailors,

farmers) has more say than another. This is a brilliant

stroke: each deme retains control over its own local affairs,

and each deme contributes adult male citizens to the Assembly,

the new democratic ruling body of Athens.

Any public structure carries the mark of the deme (DHMOS),

and I was tickled to find evidence of this even in the

municipalities of modern Greece. Here are two garbage cans,

one in Athens

(AQHNAIWN)

and the other in Pylos

(PULOU),

which clearly show the cities' pride in public works: |

|

|

| At

the end of the 6th century B.C., Athens is in perfect position

for her next move: the progression has advanced from the

hereditary monarchy in the Bronze Age to the development of

aristocratically-run poleis in the Archaic Age. Soon will come

the Age of Democracy - the Golden Age of Athens - a fifty-year

window of opportunity that closes all too soon during the Classical

Age. But first, Greece must survive the Persian

Wars... |

|

|

The

Archaic Age is best known as the Age of Aristocracies, because

its developing poleis (city-states) are

characterized by a rejection of the old-style monarchies of

the Mycenean Age (as

dramatized in later plays you may have read such as Aeschylus'

Agamemnon and Sophocles' Oedipus).

The

Archaic Age is also characterized by the development of

Panhellenic Centers, one of the first signs that Greece is

coming out of the previous period, known as the Dark Age. The

destruction of Mycenean civilization caused a fearful time in

which the Greeks of each area kept to themselves (which is

very easy to do in Greece since the mountainous topography

naturally isolates each habitable area from the next). The

establishment of the Panhellenic ("All-Greece")

Festival at Olympia (in honor Zeus) is the first sign that

Greeks are beginning to communicate and interact with each

other again. They came from all over to compete for the honor

of their home city-state.

The

Archaic Age is best known as the Age of Aristocracies, because

its developing poleis (city-states) are

characterized by a rejection of the old-style monarchies of

the Mycenean Age (as

dramatized in later plays you may have read such as Aeschylus'

Agamemnon and Sophocles' Oedipus).

The

Archaic Age is also characterized by the development of

Panhellenic Centers, one of the first signs that Greece is

coming out of the previous period, known as the Dark Age. The

destruction of Mycenean civilization caused a fearful time in

which the Greeks of each area kept to themselves (which is

very easy to do in Greece since the mountainous topography

naturally isolates each habitable area from the next). The

establishment of the Panhellenic ("All-Greece")

Festival at Olympia (in honor Zeus) is the first sign that

Greeks are beginning to communicate and interact with each

other again. They came from all over to compete for the honor

of their home city-state.

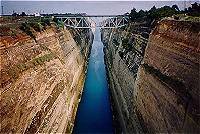

about a decade later (560's B.C.) the Isthmian Games

are founded (honoring Poseidon at Isthmia). "Isthmia"

is where we get the word "isthmus" -

this is the city on the bridge of land that joins

the southern land-mass of Greece, the Peloponnesus,

with Sterea Ellada, or Central Greece. Today, ships

can sail right through the Corinth Canal (photo on

right), but in antiquity, boats had to be dragged

across a mile-wide strip of land called the Diolkos

if they didn't want to have to sail all the way

around the southernmost tip of Greece.

about a decade later (560's B.C.) the Isthmian Games

are founded (honoring Poseidon at Isthmia). "Isthmia"

is where we get the word "isthmus" -

this is the city on the bridge of land that joins

the southern land-mass of Greece, the Peloponnesus,

with Sterea Ellada, or Central Greece. Today, ships

can sail right through the Corinth Canal (photo on

right), but in antiquity, boats had to be dragged

across a mile-wide strip of land called the Diolkos

if they didn't want to have to sail all the way

around the southernmost tip of Greece.