DR.

J'S ILLUSTRATED LECTURES

The

Illustrated Mythic Hero

Illustrated Greek Theater

Illustrated Greek Drama

Illustrated Parthenon Marbles

Illustrated Road to the Recovery of

Ancient Buildings

Illustrated Greek History MENU

Bronze Age

Archaic Age

Persian Wars

Classical Age

|

|

Dr. J's

Illustrated Greek Theater

to

be read in conjunction with

Dr.

J's Illustrated Greek Drama

General

Design of a Greek Theater

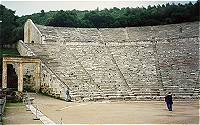

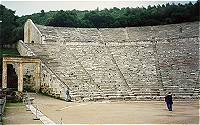

Like other significant civic

events such as assemblies and orations, the Greek theatrical

experience takes place outside in a prominently established site capable of holding

thousands of people. Up until about the time of Thespis, theatrical performances in honor

of Dionysus in Athens took place in the agora. But an accident that hurt spectators caused

the powers that be (the exact date is uncertain) to build a new theater (the

Theater of Dionysus in Athens,

photo left),

and a spot on the south slope of the Acropolis next to the already established Temple of

Dionysus Eleutherios was chosen. By the way, Eleutherios refers to the place in Boeotia

(Eleutherai) where the god first appeared in mainland Greece and where his cult worship

began. The Theater of Dionysus in Athens may have been the first theater, but the idea

caught on fast...as you can see from this selection of the 164 Greek theaters excavated in

Greece, there are 3 minimal requirements: they are all built into a hill, provide a

breathtaking view to the audience, and offer a flat performance area: Like other significant civic

events such as assemblies and orations, the Greek theatrical

experience takes place outside in a prominently established site capable of holding

thousands of people. Up until about the time of Thespis, theatrical performances in honor

of Dionysus in Athens took place in the agora. But an accident that hurt spectators caused

the powers that be (the exact date is uncertain) to build a new theater (the

Theater of Dionysus in Athens,

photo left),

and a spot on the south slope of the Acropolis next to the already established Temple of

Dionysus Eleutherios was chosen. By the way, Eleutherios refers to the place in Boeotia

(Eleutherai) where the god first appeared in mainland Greece and where his cult worship

began. The Theater of Dionysus in Athens may have been the first theater, but the idea

caught on fast...as you can see from this selection of the 164 Greek theaters excavated in

Greece, there are 3 minimal requirements: they are all built into a hill, provide a

breathtaking view to the audience, and offer a flat performance area:

|

|

|

|

isle

of Delos |

Delphi |

The

Orchestra

|

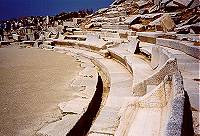

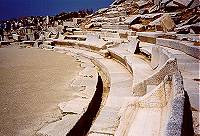

Even the most primitive of Greek

theaters had the most important of these elements: the orchestra, or

"dancing-place." It was in this circular area that the chorus, a group of 12-15

actors in a single unit, sang and danced. In the archaic Theater of Dionysus in

Athens (left),

the original orchestra floor was just smoothed dirt and was eventually replaced with

polished stone as the architecture of theater evolved. In the center of the orchestra

there was an altar to the god Dionysus where a flute player was stationed. |

|

|

|

|

Delphi |

Chaironea |

The

Theatron

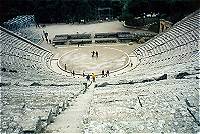

Classical

theater is all about spectacle. In Greek, theaomai means "to view" and theatai

were the people who viewed the performance, or the "spectators" in a theatron,

or "viewing area." Roman "auditorium," conversely, comes from the

Latin word audio, "to hear." Everyone in the Greek theater was assured

a clear view of the orchestra and the stage (there were no support pillars that could

block one's view) and since the theater is built into an already existing hill, the seats

are naturally arranged on an upward slope, assuring that each tier of seats is above the next. But even though the designing

focus was on a good viewing area, the Greek theater boasts magical acoustic properties as

well. A single individual's voice - or even the sound of a match being struck - rises

clearly to the uppermost seats, unless it is overpowered by a raucous chorus of

competing crickets, of course, a particularly vexing problem at Epidavros,

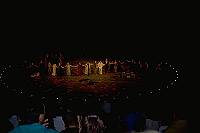

which is in a wooded setting. Below are two views of the orchestra from an excellent

vantage point (not the cheap seats!)

|

|

|

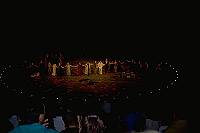

a

1996 practice session |

1998

performance of Sophocles' Electra at the Theater of Epidavros |

Some people, of

course, were given preferential treatment: most theaters (like Delos, below left, and

Athens, below right) have a row of specially designed seats nearest the orchestra for

dignitaries, judges and priests. The

Theater of Dionysus in Athens

even

has a Throne just for the officiating Priest of Dionysus. And boy, do I wish I had a

photographic record of the time the Greek Navy (in their dress whites!) was escorted into

the Theater of Epidavros and seated stage center, the best seats in the house. The entire

audience gave them a rousing standing ovation that lasted for minutes.

|

|

|

Delos |

Athens |

|

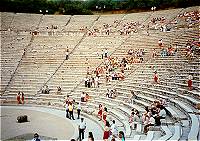

But

the rest of the 15,000 or so people who filled the theatron of a

classical theater got to their seats by climbing the stairwells made for

that purpose. In a typical theater, radial stairs divide the theatron

into kerkides, or wedge-shaped seating areas (left, Theater of

Dionysus, Athens). A walkway called a diazoma (below left,

Epidavros), divides the upper story of the theatron from the lower

portion closer to the orchestra. The diazoma

allows for a whole new arrangement of stairwells in the upper story: as

the seating area spreads wider, more stairs are necessary for safe and

comfortable access (below right, Epidavros). |

Like

the the theater in Epidavros, most

extant theaters date back only to Hellenistic Greece (3rd-2nd century BC), but the Archaic

theater in Thorikos (the American School for Classical Studies in Athens' first

excavation!), is the earliest stone theater in Greece, with parts dating to the 6th

century BC ... and it is not round: its cavea is rectangular. Is it Like

the the theater in Epidavros, most

extant theaters date back only to Hellenistic Greece (3rd-2nd century BC), but the Archaic

theater in Thorikos (the American School for Classical Studies in Athens' first

excavation!), is the earliest stone theater in Greece, with parts dating to the 6th

century BC ... and it is not round: its cavea is rectangular. Is it possible that round theaters were a later development? Thorikos' theater has only twostairways, which

divide the theatron into three sections: the central section is a nearly perfect

rectangle, while the two edge sections are curved in. The upper rows of the theatron were

accessed by stairways, and the corbelled archway over one ramp survives (photo on right).

possible that round theaters were a later development? Thorikos' theater has only twostairways, which

divide the theatron into three sections: the central section is a nearly perfect

rectangle, while the two edge sections are curved in. The upper rows of the theatron were

accessed by stairways, and the corbelled archway over one ramp survives (photo on right). |

The

seating areas of most classical theaters

are not especially well-preserved (many of the

limestone blocks were carted away to be used as building materials in ages subsequent to

antiquity). For example, although the orchestra of the theater on Delos is in good shape,

the theatron is an almost unrecognizable mess of stone (photo on right). |

Although the

upper seats of the theater of Dionysus in Athens are all but gone, some of the lower seats

survive intact from the fourth century BC and show a superb attention to detail: the seats

are designed to allow 13 inches of foot room so that every spectator can sit comfortably

with his heels back (photo on left). Although the

upper seats of the theater of Dionysus in Athens are all but gone, some of the lower seats

survive intact from the fourth century BC and show a superb attention to detail: the seats

are designed to allow 13 inches of foot room so that every spectator can sit comfortably

with his heels back (photo on left). |

|

As the seating area of a theater

became enlarged, it became necessary to build supporting walls for the theatron called analemmata.

Shown below is the particularly well articulated analemma from the theater at Delos: |

The

Skene

One of the first

modifications to the basic performance area of archaic theaters was the addition of a

portable wooden stage area, which was later replaced with a more permanent design. By the

time of Aeschylus, the skene came complete with a painted (probably) facade representing

the power source of the play, usually a palace or temple. The backdrop also included a

door, through which actors could enter and exit the performance area. Murders and other

violent scenes were usually performed out of sight of the audience, "behind closed

doors." Therefore, classical theater often resorted to the use of a wheeled cart

called an ekkyklema to divulge the activity acted out "behind the

scenes." The most typical burdens of the ekkyklema was the corpse of a

murdered individual.

The

circular pathway that surrounds the orchestra is called the parodos and can be

accessed from either side of the skene. The parodos is an important element of

the Greek theater and serves a double purpose: first, it provides the audience with a way

to access their seats. More importantly for the purpose of staging the play, though, it

provides access to the chorus and some actors to the orchestra. The chorus never entered

the orchestra from the skene, and some characters are denied access because they lack the

might and right to be associated with the power structure represented by the

skene:

messengers, visitors, exiles, etc (see mini-lecture below for an example of staging a

Greek play). It is not uncommon, however, for characters to move freely between the skene

and the orchestra. In the case of human beings, ramps or stairways serve their purpose,

but in the case of divine messengers or visitors, a mechane (crane) would lift

them bodily into the air. The

circular pathway that surrounds the orchestra is called the parodos and can be

accessed from either side of the skene. The parodos is an important element of

the Greek theater and serves a double purpose: first, it provides the audience with a way

to access their seats. More importantly for the purpose of staging the play, though, it

provides access to the chorus and some actors to the orchestra. The chorus never entered

the orchestra from the skene, and some characters are denied access because they lack the

might and right to be associated with the power structure represented by the

skene:

messengers, visitors, exiles, etc (see mini-lecture below for an example of staging a

Greek play). It is not uncommon, however, for characters to move freely between the skene

and the orchestra. In the case of human beings, ramps or stairways serve their purpose,

but in the case of divine messengers or visitors, a mechane (crane) would lift

them bodily into the air.

Eisodoi are

the ramps that give access to the paradoi, and the Romans were particularly fond

of creating elaborate stage areas. The archway in the photo on the left at Epidavros would

have covered the stage left eisodos. |

|

The Romans also

greatly elaborated upon the simple Greek skene itself. On the left is the little theater

at Oropos, with its accompanying Roman stoa, the sort which is usually two-storied and is

used as a storage area for scenery and props, as well as the actors' changing room. On the

right is the celebrated Bema of Phaedrus, a Roman addition to the theater of Dionysus in

Athens.

|

|

|

|

Oropos |

Athens |

The Staging of Play

The purpose of this section

is to prove the usefulness of knowing this information. Words in

blue were introduced in this lecture. It can

be helpful to know how the playwright would have used the different parts of the classical

theater to stage his play. The

orchestra was the chorus' domain; actors generally remained on the

skene

unless they entered the performance area through a

parodos directly onto the

orchestra. It is important to remember that the

skene represents the power source

in the play. Such knowledge can help to illuminate the underlying themes of a play. For

example:

In the Agamemnon, the

skene

is dressed to look like the Palace at Mycenae (Argos). Who enters the

performance area through the double doors of the

skene?

Clytemnestra. Who is in charge? Clytemnestra. Agamemnon, the King,

arrives home after the war, but enters directly into the

orchestra (via the

parodos)

in his chariot and joins the multitude outside the royal house, like any other citizen of

the city (represented by the chorus, already inhabiting that space) - this is a clear signal that he does not

hold the upper hand in his own house. He eventually does pass through the doors of the

skene - and the next time we see

him, he is being wheeled out through those doors again - a corpse on the

ekkyklema.

After the murders of

Cassandra and Agamemnon, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus make a final appearance, passing

through the double doors of the

skene one more time to appear before the people of Argos as their King and

Queen. A nice touch is that this scene is replayed in reverse in The Libation Bearers

- the second play of the trilogy - when it is Orestes who begins as a visitor in his own

home, is welcomed into the royal house through the door of the

skene, and then wheels the corpses of

Aegisthus and Clytemnestra out through the same double doors on the same

ekkyklema they used in the first play.

Tour theaters I don't have

pictures of!

Learn more about Greek

Stagecraft including the buildings, scenery, props and actors' masks.

See some great aerial views of

these theaters and others

|