DR.

J'S ILLUSTRATED LECTURES

The

Illustrated Mythic Hero

Illustrated Greek Theater

Illustrated Greek Drama

Illustrated Parthenon Marbles

Illustrated Road to the Recovery of

Ancient Buildings

Illustrated Greek History MENU

Bronze Age

Archaic Age

Persian Wars

Classical Age

|

|

Dr. J's Illustrated

Road to the Recovery

of Ancient Buildings

| How many of us are

surprised when we tour Greece (virtually or otherwise) to find that 5th century BC ruins

are lying about waiting for us to inspect them even though 2500 years of human history and

natural process intervenes between us and them? No, ancient Greece has not been kept under

a bell jar - indeed, it is amazing that so much of this long-lost culture has been

uncovered even though the land has been continually inhabited and developed since

antiquity. Excavation and restoration programs have done wonders in the face of the

natural and man-made changes wrought over these last two and one-half

millenia. Here is a

brief introduction to the subject of exactly what kind of stumbling blocks stand in the

way of rediscovering the grandeur of these mute witnesses to history. Originally, I wrote

this lecture only about the buildings on the Acropolis, but other places in Greece offer

excellent material as well. |

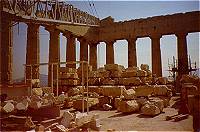

Presently, the biggest

program in the works concerns the Restoration of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens.

Cranes, such as the one in this 1995 picture of the inside of the Parthenon, are used to

hoist newly hewn marble pieces cut to replace those lost to time, war and

treasure-seekers. Marble is being quarried from the same mountain - Mt. Pendeli -

that supplied the original building material between 447-432 BC. The nine miles distance

between source and destination makes that ancient accomplishment all the more astounding. Presently, the biggest

program in the works concerns the Restoration of the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens.

Cranes, such as the one in this 1995 picture of the inside of the Parthenon, are used to

hoist newly hewn marble pieces cut to replace those lost to time, war and

treasure-seekers. Marble is being quarried from the same mountain - Mt. Pendeli -

that supplied the original building material between 447-432 BC. The nine miles distance

between source and destination makes that ancient accomplishment all the more astounding.  The other buildings on the Acropolis are also being restored

to their fifth century appearance. Here is the Temple of Athena Nike under wraps in 1998

(left) and without scaffolding in 1996 (right). The other buildings on the Acropolis are also being restored

to their fifth century appearance. Here is the Temple of Athena Nike under wraps in 1998

(left) and without scaffolding in 1996 (right). |

acts

of war

In 1687,

the Venetians attacked the Turks (just like in Othello!), who were garrisoned on

the Acropolis. Venetian strikes exploded an arsenal of gunpowder stored in the Parthenon,

taking the roof off, destroying 28 columns and most of the interior cella, and starting a

fire that burned for 2 days. The cannonballs shot from Philopappos Hill (right) also left

their mark (left).

|

natural

calamities

Several

buildings on the Acropolis have also suffered damage from natural causes. The Propylaia was damaged severely in 1645 when

lightning struck another Turkish gunpowder store (if that can be chalked up to

"natural causes"), and the Parthenon moved an inch off its foundation during an

earthquake in 1981. But such earthquake and storm damage is common to antiquities in

Greece:

|

On the left is a close-up

of what remains of the Temple of

Olympian Zeus in Athens (NOT on the Acropolis, though). The column in the foreground

fell during a terrific rainstorm in 1852. On the right, an earthquake toppled these

columns of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia

(NOT Athens), leaving perfect rows of tinker-toy-like column drums of the building which

once housed a Wonder of the Ancient World, the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of

Zeus. On the left is a close-up

of what remains of the Temple of

Olympian Zeus in Athens (NOT on the Acropolis, though). The column in the foreground

fell during a terrific rainstorm in 1852. On the right, an earthquake toppled these

columns of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia

(NOT Athens), leaving perfect rows of tinker-toy-like column drums of the building which

once housed a Wonder of the Ancient World, the chryselephantine (gold and ivory) statue of

Zeus.

|

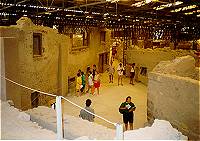

In 1450 BC, a fantastic

volcanic explosion caused a significant amount of havoc in the ancient world. The recently

dug-up town of Akrotiri, on the island of Santorini,

was buried under 150 feet of pumice rock that rained down on the island during the

eruption - about 1500 years before Vesuvius buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. In 1450 BC, a fantastic

volcanic explosion caused a significant amount of havoc in the ancient world. The recently

dug-up town of Akrotiri, on the island of Santorini,

was buried under 150 feet of pumice rock that rained down on the island during the

eruption - about 1500 years before Vesuvius buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. |

metal

harvesting

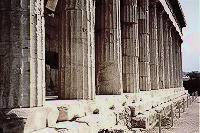

The Hephaesteum, in the Athenian Agora, is the

best preserved Doric Temple in all of mainland Greece because it became a Christian Church

very early in late Antiquity (about AD 200). But in Medieval Times, its iron clamps were

harvested from its joints so that the metal could be melted down to make weapons and

ammunition. Chisel holes are clearly evident along the length of the

crepidona, or top

step of the foundation. The Hephaesteum, in the Athenian Agora, is the

best preserved Doric Temple in all of mainland Greece because it became a Christian Church

very early in late Antiquity (about AD 200). But in Medieval Times, its iron clamps were

harvested from its joints so that the metal could be melted down to make weapons and

ammunition. Chisel holes are clearly evident along the length of the

crepidona, or top

step of the foundation.

|

|

Although the church's efforts preserved the

building itself, the art work was not as fortunate. The metopes of the Hephaesteum

dramatize Theseus' fight against the Minotaur (half man/half bull), a fact that caused

this building mistakenly to be called the Theseion for generations. But Theseus has lost

his head to a chisel in all the metopes, while the Minotaur suffered no such insult: in

the eyes of the church, it was worse to be a pagan than a monster. Although the church's efforts preserved the

building itself, the art work was not as fortunate. The metopes of the Hephaesteum

dramatize Theseus' fight against the Minotaur (half man/half bull), a fact that caused

this building mistakenly to be called the Theseion for generations. But Theseus has lost

his head to a chisel in all the metopes, while the Minotaur suffered no such insult: in

the eyes of the church, it was worse to be a pagan than a monster. |

environmental

issues

Earthquakes,

thunderstorms, lightning strikes, cannonball assaults, gunpowder explosions,

re-structuring, treasure-seeking and willful mutilation have certainly taken their toll on

the buildings on the Acropolis in Athens. But more damage has been suffered in the

past fifty years than in the preceding two millenia: air pollution caused by automobile

exhaust is literally eating away the marble of Athens' ancient shrines.

|

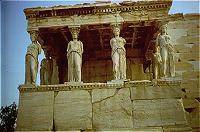

This Caryatid

(left) - a marble column shaped like a woman - was taken from the south porch of the

Erechtheum to England by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century and therefore escaped the

fate of her five ravaged sisters, who now look like melted wax images whose detail has

worn away. In 1979 they were moved inside a nitrogen-filled tank inside the Acropolis

Museum. The columns seen today holding up the Erechtheum's South Portico (right) are

plaster replicas. This Caryatid

(left) - a marble column shaped like a woman - was taken from the south porch of the

Erechtheum to England by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century and therefore escaped the

fate of her five ravaged sisters, who now look like melted wax images whose detail has

worn away. In 1979 they were moved inside a nitrogen-filled tank inside the Acropolis

Museum. The columns seen today holding up the Erechtheum's South Portico (right) are

plaster replicas.

|

| Lord

Elgin took much more away from the Acropolis than just the one Caryatid. Below is a

sampling of the Parthenon sculptures, popularly called the Elgin Marbles, that the British

Museum bought from Elgin in 1816. Dr. J's

Illustrated Parthenon Marbles page offers a bigger selection and fuller commentary. |

|

|

|

| pedimental sculpture |

frieze |

metope |

Much ancient sculpture has been lost

permanently because of such interest, and much has just been relocated by subsequent

invaders: for example, in 86 BC Sulla removed two of the Corinthian-style columns from the

Temple of Olympian Zeus built by Hadrian for the Temple on the Capitoline in Rome.

To reinvent the Acropolis in Pericles' model, archaeologists are engaged in collecting and

cataloguing the fragments scattered about and putting the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle back together. In the photo on the

right is a small sampling of the outrageous number of marble fragments that patiently

await the conservators in their quest to reconstruct the Propylaia. putting the pieces of the jigsaw puzzle back together. In the photo on the

right is a small sampling of the outrageous number of marble fragments that patiently

await the conservators in their quest to reconstruct the Propylaia.

|

botched

past restoration attempts |

Mr.

Tanoulas, director of

the Propylaia Restoration Project, points out grievous faults caused by an earlier

reconstruction attempt by Balanos which modern conservators must repair before the current

work of restoration can occur. On the left Mr.

Tanoulas, director of

the Propylaia Restoration Project, points out grievous faults caused by an earlier

reconstruction attempt by Balanos which modern conservators must repair before the current

work of restoration can occur. On the left  Mr. Tanoulas

points to holes drilled in the marble to aid in lifting them. These were foolishly left

open to the air, and pooled water damaged the marble. He also used iron clamps, which

subsequently rusted, expanding and cracking the marble. In antiquity they knew better -

they coated their iron clamps with lead. Balanos also erred by "reconstructing"

this Ionic column capital (on the right) from marble fragments really belonging to four

distinct column capitals. Mr. Tanoulas

points to holes drilled in the marble to aid in lifting them. These were foolishly left

open to the air, and pooled water damaged the marble. He also used iron clamps, which

subsequently rusted, expanding and cracking the marble. In antiquity they knew better -

they coated their iron clamps with lead. Balanos also erred by "reconstructing"

this Ionic column capital (on the right) from marble fragments really belonging to four

distinct column capitals. |

|

A series of three

photos showing conservators reconstructing a piece of the Propylaia entablature: (1) a

crane is used to hoist one piece of marble onto another for refitting; (2) titanium rods

have replaced any iron implanted by Balanos and cement has been poured into any remaining

holes; (3) a perfect fit! |

copyright

2001 Janice

Siegel,

All Rights Reserved

send comments to: Janice Siegel (jfsiege@ilstu.edu)

date this page was edited last:

11/26/2005

the URL

of this page:

|