|

|

||||||||

|

Courses Taught INTELLECTUAL HERITAGE (at Temple

University) Delphi- A Focal Point for IH 51 Texts Subject Study Aids: Aeschylus' Libation Bearers Study Guide Sophocles' Oedipus and the Sphinx Lecture Dr. J's Illustrated Pericles' Funeral Oration Dr. J's Illustrated Pericles and America Dr. J's Illustrated Pericles and Philadelphia Dr. J's Illustrated Aeschylus' Oresteia Dr. J's Curse of the House of Atreus Outline Dr. J's Background Lecture on Greek Philosophy Dr. J's Apology Study Questions Dr. J's Illustrated Plato's Apology Socrates and the Apology Lecture Epic Qualities of the Sundiata Lecture RELIGIOUS FOUNDATIONS OF CLASSICAL GREECE Courses Proposed Religious Foundations of Greek Culture The Intersection of Myth and History The Ancient Greek Cultural Nexus- Art, Archaeology, Literature and Topography |

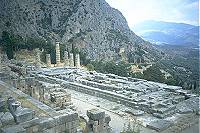

From 1996-2001 I taught in the Intellectual Heritage Program at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. This page is part of my teaching materials for Intellectual Heritage 51, a course covering literature and ideas from Sappho through Shakespeare... Visit Dr. J's Illustrated Delphi for a thorough exploration of the archaeological site.

Delphi:

A Focal Point for by Dr. Janice Siegel ATTENTION

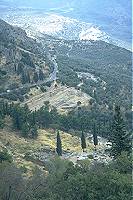

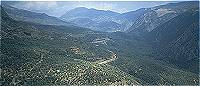

(with all due respect to Dr. Peter Liacouris, for whom the Temple of Apollo has been renamed since I wrote the above joke) Many of the texts we encounter in IH51 reveal man's unquenchable desire to determine his place in the world and universe. The pre-Socratic cosmologists of the ancient Greek world lay the foundation for Galileo's musings in natural science, while Plato and the Sacred Texts struggle to understand how man can lead a more fulfilled life whether it is by accessing the Creator or the Realm of ideas. Our IH51 texts show that men of all cultures, times and heritages seek to belong to something bigger than they are, to integrate themselves into the cosmological model. Although the goal is generally the same, the path each text follows is distinctly marked by the culture which generates it. For the Greeks, one image pops up over and over again as a source of inspiration, security and knowledge beyond our experience: the sacred site of Delphi and the Oracle, named by the geographer Strabo as the most reliable oracle of the Greek world. Delphi is an important site in Greek history and Greek literature. In fact, it figures prominently in almost every one of the texts on our IH51 syllabus. First, let's put Delphi in its proper historical, political and religious context...not an easy task. In order to find out why so much of Greek literature and thought revolved around Delphi, we go first to mythology... Delphi was one of only four Panhellenic ("All-Greece") sites in ancient Greece - the most famous of which is Olympia, the other two being Nemea and Isthmia. Every two or four years, depending on the site, Greeks from all corners of the Greek world came to show their respects to the patron deity of the site by competing in literary, athletic and theatrical competitions for the honor of their hometown. Like all the other Panhellenic Games sites, Delphi also sported a stadium, a theater, and an area where the athletes could train and live for three months before the games. In Aeschylus' Libation Bearers, Orestes chooses the Pythian Games (Delphi equivalent to "Olympic") as the site of his made up death: in his made-up tale, he dies in a chariot race accident while pursuing the glory all Greeks would risk their lives for.

The Oracle of Delphi even pops up in Plato's Apology! Socrates can argue the charge of impiety leveled against him by pointing to a prophecy of this same Oracle. Socrates claims that his friend Chaerophon, now dead, once was told by the Oracle that there was no man wiser than Socrates. During his trial, Socrates claims that he honors the god - and in fact does the god's work by proving the validity of the Oracle - by questioning those around him so he can learn exactly what the Oracle's words mean. He comes to the conclusion, of course, that his wisdom lies in his realization of his own ignorance. In the spirit of eradicating all things pagan, the Pope Theodosius closed the Oracle of Delphi at the end of the fourth century AD, about the same time he officially ended the Olympic Games, and for the same reason.

copyright

2001 Janice

Siegel,

All Rights Reserved

date this page was edited last:

10/25/2005 |

||||||||

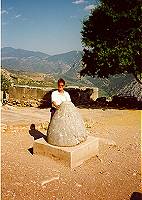

Oracle) and Oedipus (on his way to

the oracle) have their fatal meeting at a crossroads near Delphi (like this one at the

right, but not this one at the right). And, of course, it is everyone's frantic

desire to avoid the various prophesies of the Oracle that drives the action of the play.

Oracle) and Oedipus (on his way to

the oracle) have their fatal meeting at a crossroads near Delphi (like this one at the

right, but not this one at the right). And, of course, it is everyone's frantic

desire to avoid the various prophesies of the Oracle that drives the action of the play.